non-fiction

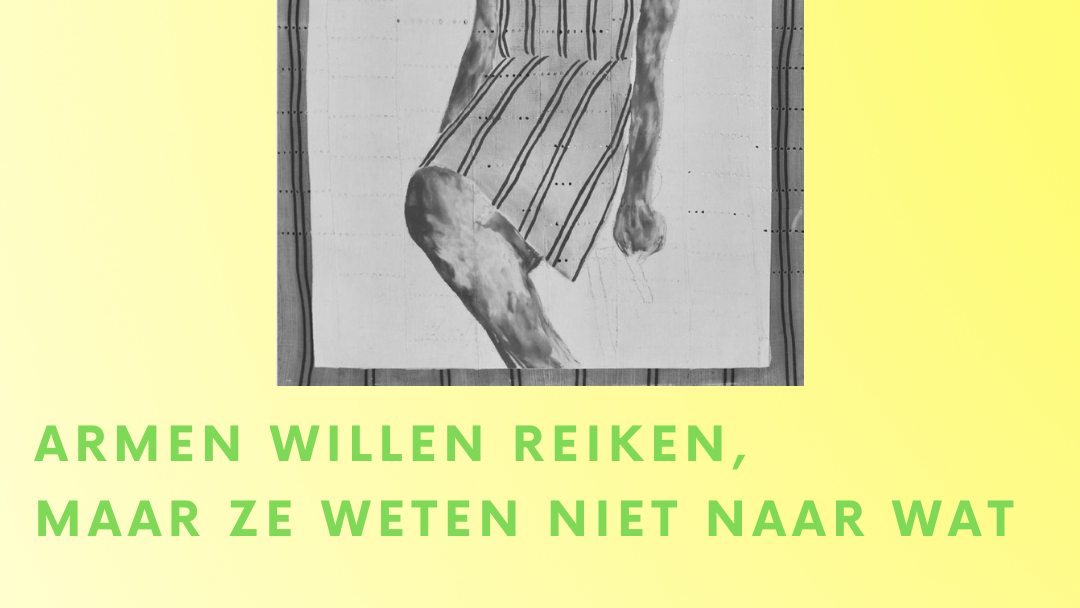

As I am translating Kae Tempest’s Paradise to Dutch, a play about the Greek soldier Philoctetes who got wounded in the Trojan War (as they all did, didn’t they) and then got dumped on an island by Odysseus (always him), where his wound never healed and reeked of death, I am thinking about how visceral they write, how embodied the story is, and how on earth I am going to translate this text and play the part of Philoctetes coming from a household where everything related to the body took up so much space, it became an transparent elephant in a cerebral room,

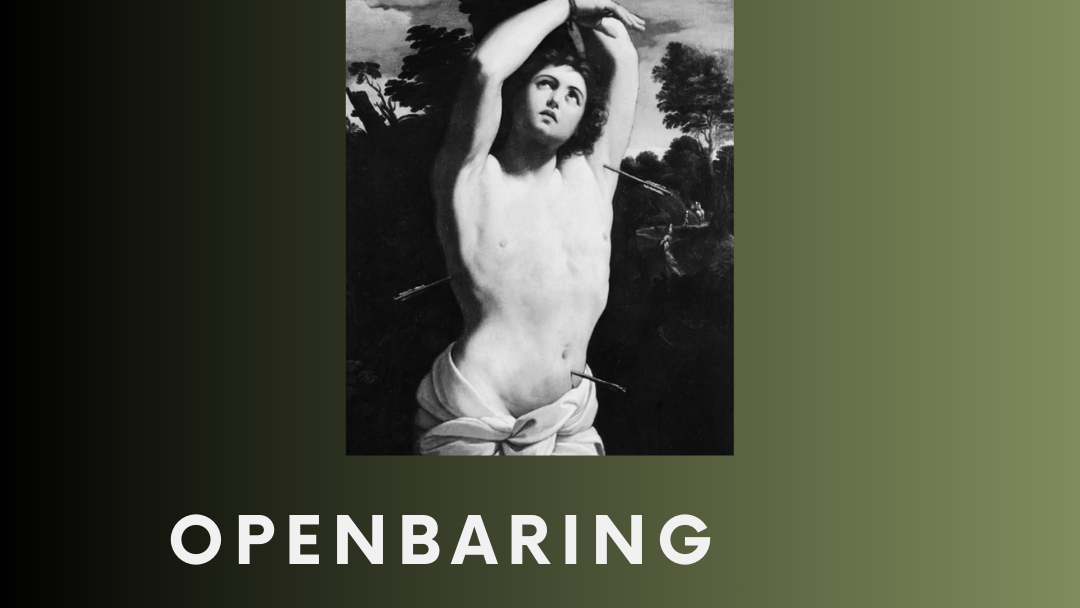

As I am being told by a woman on the street that Jesus loves me, that there will be a life after this one, an eternal life without suffering, a Paradise, and that all I need to do is marry a man who is waiting for me somewhere because I am God’s queen and this is what he has in store for me,

As I am noticing her tone is changing when she tells me my lesbianism will destroy me, I am trying not to laugh to not disrespect her, I take the bible she gives me, and I try to see it as a pleasant conversation, although I know she thinks I will burn in a place especially reserved for people like me,

As I am doing my make up with knowledge in both of my hands, remembering a ritual I have been creating for the past seven years, I wish I was born a man, so that I could dress femme, and people would wonder which gender I am and decide it has to be non-binary, because what else would they,

As I can’t stop thinking about the phrase from Sex Education’s Cal when Jackson tells them he doesn’t think he’s queer: “I’m afraid you’ll keep seeing me as a woman” and he can neither deny nor confirm,

As I can’t stop thinking about the phrase from Sex Education’s Cal when Jackson tells them he doesn’t think he’s queer: “I’m afraid you’ll keep seeing me as a woman” and he can neither deny nor confirm,

As you are fucking me in the car, in the woods, in the bed, in the kitchen, spitting in my mouth, slapping me in the face, grabbing my breasts, choking me with all sorts of body parts, making me come repeatedly, I am thinking nothing,

As I am trying to match the rhythm, the poetry and the cadence of your body, of my muscle memory and of Paradise (x2), I am thinking nothing but: in pleasure we unite.

-------

You have an ‘odi et amo’ relationship with psychoanalysis and you are trying to "queer your way through life", a quote by a professor of yours when you asked her if me being non-binary makes you queer, (“It doesn’t” she said, “it makes you ‘queering’”) and these two collide in the book you’re reading: ‘Can The Monster speak’ by Paul C. Preciado. You want me to read it, because it’s probably the only accessible book by the writer. We’re in a coffee bar, I take the copy and your pastel yellow highlighter, and I tell you you shouldn’t only highlight the important things, but also the poetry beneath it all. You don’t tend to do that, so I decide that’s on me now, and I start.

On November 17, 2019, Paul Preciado gave a speech at a psychoanalysis conference for “Women in Psychoanalysis”. He was never able to finish that speech. After a quarter of what he had prepared, he was booed out of the conference hall.

Preciado later published his text under the name "Can the Monster Speak" after the chaotic fragments recorded on blurry cell phones by angry psychoanalysts ran rampant online.

Although I have been in analysis for over a year now, I know too little about Freud and Lacan to be able to reproduce or interpret what Preciado was trying to tell the angry flock of psychoanalysts. I know my psychoanalyst doesn't quite understand what I mean when I say I don't feel like a woman, I know she likes to link everything I do to my parents and I know that when she talks about love, sex and relationships, she always does it in relation to men, even though there are quite a few more gender identities swimming in my dating pool.

I do know enough about gender dysphoria, the hatred for heteronormative patriarchy, and the clear definitions of identity that release others from their position to understand what Preciado means when he talks about himself and his role in this society.

And I agree.

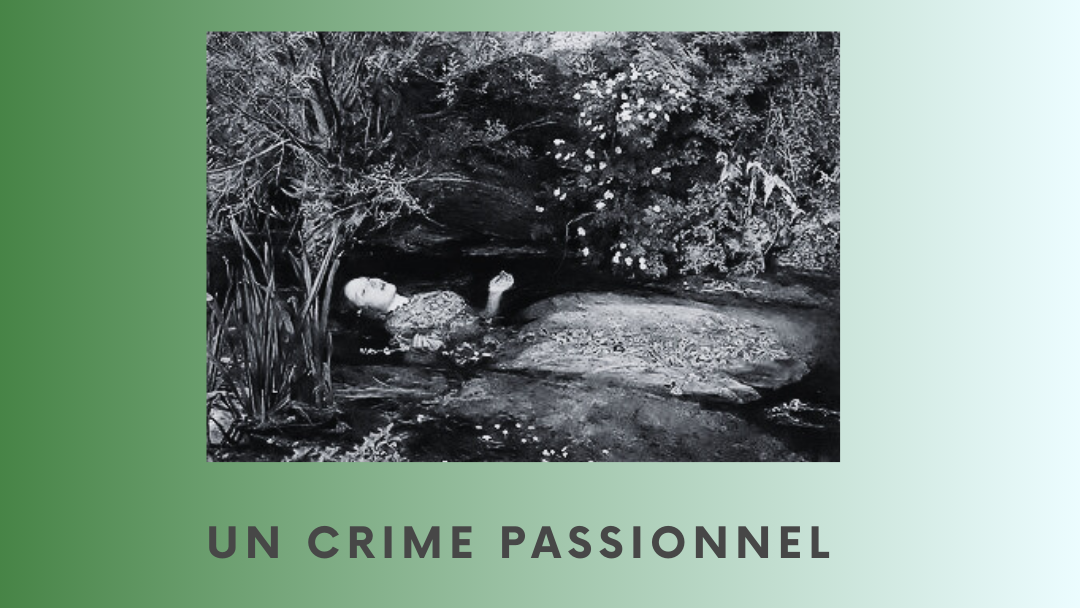

There is something unbearably claustrophobic about being a woman. It is in the heavily loaded art history: it is the two options you are condemned to, it is the fatality, it is the fragility, it is the never ending violence. It is the body parts that will never be your own. It is an appearance that will never be right. It's a battle, my body is a battle, my body is a battlefield for violence and penetration, a frontline that takes on attack after attack, and when it finally breaks, it welcomes the enemy into a blood-soaked, arid terrain.

A (no) man's land. Up for grabs.

In an effort to set up my own siege, I am shedding my womanhood as if it were a second skin.

So I keep reading the book, and on page 22 Preciado asks “What is it in a child's body that determines your whole life for you?”

“You could scratch yourself until you bled and not find an answer. You could split your head open on the steel bars of gender and not discover the reason.”

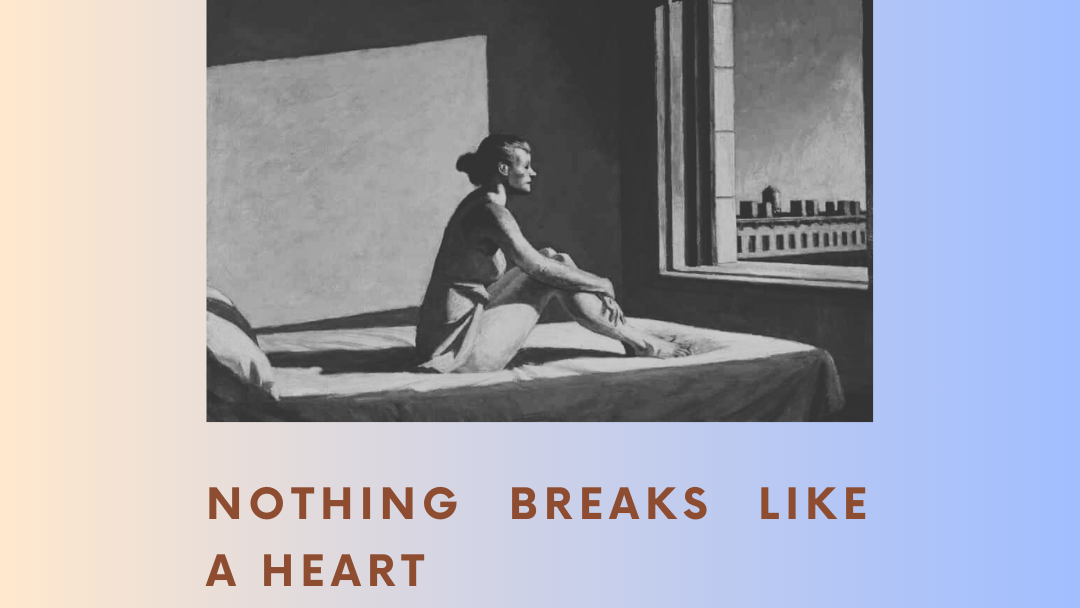

And as I am looking at the pile of shedded skin, I realise I freed myself from the dead weight I was carrying with me for all these years. But the cage remains.

There is no liberation in my identity, and there will never be freedom. Preciado and I both know that. I told my psychoanalyst that I feel freer, but that feeling is as constructed as my identity. A colorful mishmash of intersections, pronouns that the majority of the population don't know anything about, and above all just who I was and have been these past years: a person people perceive to be a woman.

Preciado has changed his name: Beatriz and his new pronouns couldn't coexist, his friends said. He asked a shaman what name to take, and was told it would appear in a dream. And he dreamed of a book: "Complete works of Marx including the poetry, edited by Paul B. Preciado". And there it was, his shaman confirmed: this was his name.

You ask me if I am also thinking about another name.

I do, I say, but I have no idea what it could be.

Maybe I should look for a shaman too.

Preciado later published his text under the name "Can the Monster Speak" after the chaotic fragments recorded on blurry cell phones by angry psychoanalysts ran rampant online.

Although I have been in analysis for over a year now, I know too little about Freud and Lacan to be able to reproduce or interpret what Preciado was trying to tell the angry flock of psychoanalysts. I know my psychoanalyst doesn't quite understand what I mean when I say I don't feel like a woman, I know she likes to link everything I do to my parents and I know that when she talks about love, sex and relationships, she always does it in relation to men, even though there are quite a few more gender identities swimming in my dating pool.

I do know enough about gender dysphoria, the hatred for heteronormative patriarchy, and the clear definitions of identity that release others from their position to understand what Preciado means when he talks about himself and his role in this society.

And I agree.

There is something unbearably claustrophobic about being a woman. It is in the heavily loaded art history: it is the two options you are condemned to, it is the fatality, it is the fragility, it is the never ending violence. It is the body parts that will never be your own. It is an appearance that will never be right. It's a battle, my body is a battle, my body is a battlefield for violence and penetration, a frontline that takes on attack after attack, and when it finally breaks, it welcomes the enemy into a blood-soaked, arid terrain.

A (no) man's land. Up for grabs.

In an effort to set up my own siege, I am shedding my womanhood as if it were a second skin.

So I keep reading the book, and on page 22 Preciado asks “What is it in a child's body that determines your whole life for you?”

“You could scratch yourself until you bled and not find an answer. You could split your head open on the steel bars of gender and not discover the reason.”

And as I am looking at the pile of shedded skin, I realise I freed myself from the dead weight I was carrying with me for all these years. But the cage remains.

There is no liberation in my identity, and there will never be freedom. Preciado and I both know that. I told my psychoanalyst that I feel freer, but that feeling is as constructed as my identity. A colorful mishmash of intersections, pronouns that the majority of the population don't know anything about, and above all just who I was and have been these past years: a person people perceive to be a woman.

Preciado has changed his name: Beatriz and his new pronouns couldn't coexist, his friends said. He asked a shaman what name to take, and was told it would appear in a dream. And he dreamed of a book: "Complete works of Marx including the poetry, edited by Paul B. Preciado". And there it was, his shaman confirmed: this was his name.

You ask me if I am also thinking about another name.

I do, I say, but I have no idea what it could be.

Maybe I should look for a shaman too.